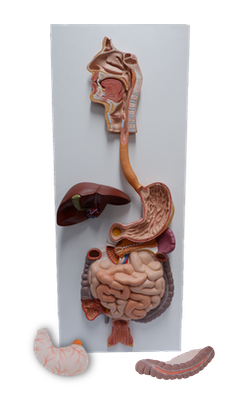

Main Model

Tooth

Teeth

The chief functions of teeth are to:

• Incise (cut), reduce, and mix food material with saliva

during mastication (chewing).

• Help sustain themselves in the tooth sockets by assisting

the development and protection of the tissues that support them.

• Participate in articulation (distinct connected speech).

The teeth are set in the tooth sockets and are used in mastication and in assisting in articulation. A tooth is identified and

described on the basis of whether it is deciduous (primary) or permanent (secondary), the type of tooth, and its proximity to the midline or front of the mouth (e.g., medial and

lateral incisors; the 1st molar is anterior to the 2nd).

Children have 20 deciduous teeth; adults normally have

32 permanent teeth. Before eruption, the

developing teeth reside in the alveolar arches as tooth buds.

The types of teeth are identified by their characteristics:

incisors, thin cutting edges; canines, single prominent

cones; premolars (bicuspids), two cusps; and molars, three

or more cusps. The vestibular surface

(labial or buccal) of each tooth is directed outwardly, and the

lingual surface is directed inwardly. As used in clinical (dental) practice, the mesial surface of a tooth is directed toward the median plane of the facial part of the cranium. The distal surface is directed away from this plane;

both mesial and distal surfaces are contact surfaces - that is, surfaces that contact adjacent teeth. The masticatory surface

is the occlusal surface.

Parts and Structure of Teeth

A tooth has a crown, neck, and root. The crown

projects from the gingiva. The neck is between the crown

and root. The root is fixed in the tooth socket by the periodontium (connective tissue surrounding roots); the number

of roots varies. Most of the tooth is composed of dentine (Latin dentinium), which is covered by enamel over the crown and cement (Latin cementum) over the root. The pulp cavity

contains connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves. The

root canal (pulp canal) transmits the nerves and vessels to

and from the pulp cavity through the apical foramen.

The tooth sockets are in the alveolar processes of the

maxillae and mandible; they are the skeletal

features that display the greatest change during a lifetime. Adjacent sockets are separated by interalveolar septa; within the socket, the roots of teeth with more

than one root are separated by interradicular septa. The bone of the socket has a thin cortex

separated from the adjacent labial and lingual cortices by a variable amount of trabeculated bone. The labial wall of the

socket is particularly thin over the incisor teeth; the reverse

is true for the molars, where the lingual wall is thinner. Thus

the labial surface commonly is broken to extract incisors and

the lingual surface is broken to extract molars.

The roots of the teeth are connected to the bone of the alveolus by a springy suspension forming a special type of fibrous

joint called a dento-alveolar syndesmosis or gomphosis.

The periodontium (periodontal membrane) is composed of

collagenous fibers that extend between the cement of the root

and the periosteum of the alveolus. It is abundantly supplied

with tactile, pressoreceptive nerve endings, lymph capillaries,

and glomerular blood vessels that act as hydraulic cushioning

to curb axial masticatory pressure. Pressoreceptive nerve endings are capable of receiving changes in pressure as stimuli.

Vasculature of Teeth

The superior and inferior alveolar arteries, branches of the

maxillary artery, supply the maxillary and mandibular teeth,

respectively. The alveolar

veins have the same names and distribution accompany the

arteries. Lymphatic vessels from the teeth and gingivae pass

mainly to the submandibular lymph nodes.

Innervation of Teeth

The named branches of the superior (CN V2) and

inferior (CN V3) alveolar nerves give rise to dental plexuses

that supply the maxillary and mandibular teeth.