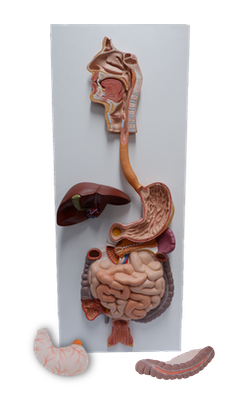

Main Model

Cardia

Stomach

The stomach is the expanded part of the digestive tract

between the esophagus and small intestine. It

is specialized for the accumulation of ingested food, which it

chemically and mechanically prepares for digestion and passage into the duodenum. The stomach acts as a food blender

and reservoir; its chief function is enzymatic digestion. The

gastric juice gradually converts a mass of food into a semiliquid mixture, chyme (Greek juice), which passes fairly quickly into

the duodenum. An empty stomach is only of slightly larger

caliber than the large intestine; however, it is capable of considerable expansion and can hold 2-3 L of food.

Position, Parts, and Surface Anatomy of Stomach

The size, shape, and position of the stomach can vary markedly in persons of different body types (bodily habitus) and

may change even in the same individual as a result of diaphragmatic movements during respiration, the stomach's

contents (empty vs. after a heavy meal), and the position

of the person. In the supine position, the stomach commonly lies in the right and left upper quadrants, or epigastric, umbilical, and left hypochondrium and flank regions. In the erect position, the stomach moves inferiorly. In asthenic (thin, weak) individuals, the body of the

stomach may extend into the pelvis.

The stomach has four parts:

• Cardia: the part surrounding the cardial orifice (opening), the superior opening or inlet of the stomach. In the

supine position, the cardial orifice usually lies posterior to the 6th left costal cartilage, 2-4 cm from the median plane

at the level of the T11 vertebra.

• Fundus: the dilated superior part that is related to the

left dome of the diaphragm, limited inferiorly by the horizontal plane of the cardial orifice. The cardial notch is

between the esophagus and the fundus. The fundus may

be dilated by gas, fluid, food, or any combination of these.

In the supine position, the fundus usually lies posterior to

the left 6th rib in the plane of the MCL.

• Body: the major part of the stomach between the fundus

and pyloric antrum.

• Pyloric part: the funnel-shaped outflow region of the

stomach; its wider part, the pyloric antrum, leads into

the pyloric canal, its narrower part. The

pylorus (Greek, gatekeeper) is the distal, sphincteric region

of the pyloric part. It is a marked thickening of the circular layer of smooth muscle that controls discharge of

the stomach contents through the pyloric orifice (inferior opening or outlet of the stomach) into the duodenum. Intermittent emptying of the stomach

occurs when intragastric pressure overcomes the resistance of the pylorus. The pylorus is normally tonically contracted so that the pyloric orifice is reduced, except when emitting chyme (semifluid mass). At irregular intervals,

gastric peristalsis pushes the chyme through the pyloric

canal and orifice into the small intestine for further mixing, digestion, and absorption.

In the supine position, the pyloric part of the stomach

lies at the level of the transpyloric plane, midway between

the jugular notch superiorly and the pubic crest inferiorly. The plane transects the 8th costal cartilages

and the L1 vertebra. When erect its location varies from the

L2 through L4 vertebra. The pyloric orifice is approximately

1.25 cm right of the midline.

The stomach also features two curvatures:

• Lesser curvature: forms the shorter concave right border of the stomach. The angular incisure (notch), the

most inferior part of the curvature, indicates the junction

of the body and pyloric part of the stomach. The angular incisure lies just to the left of the midline.

• Greater curvature: forms the longer convex left border of the stomach. It passes inferiorly to the left from

the junction of the 5th intercostal space and MCL, then

curves to the right, passing deep to the 9th or 10th left cartilage as it continues medially to reach the pyloric antrum.

Because of the unequal lengths of the lesser curvature on the

right and the greater curvature on the left, in most people the

shape of the stomach resembles the letter J.

Interior of Stomach

The smooth surface of the gastric mucosa is reddish brown during life, except in the pyloric part, where it is pink. In life, it is

covered by a continuous mucous layer that protects its surface

from the gastric acid the stomach's glands secrete. When contracted, the gastric mucosa is thrown into longitudinal ridges or

wrinkles called gastric folds (gastric rugae);

they are most marked toward the pyloric part and along the

greater curvature. During swallowing, a temporary groove

or furrow-like gastric canal forms between the longitudinal

gastric folds along the lesser curvature. It can be observed

radiographically and endoscopically. The gastric canal forms

because of the firm attachment of the gastric mucosa to the

muscular layer, which does not have an oblique layer at this

site. Saliva and small quantities of masticated food and other

fluids drain along the gastric canal to the pyloric canal when

the stomach is mostly empty. The gastric folds diminish and

obliterate as the stomach is distended (fills).

Relations of Stomach

The stomach is covered by visceral peritoneum, except where

blood vessels run along its curvatures and in a small area posterior to the cardial orifice. The two layers of

the lesser omentum extend around the stomach and leave its

greater curvature as the greater omentum. Anteriorly, the stomach is related to the diaphragm,

left lobe of liver, and anterior abdominal wall. Posteriorly, the

stomach is related to the omental bursa and pancreas; the posterior surface of the stomach forms most of the anterior wall of

the omental bursa. The transverse colon is related

inferiorly and laterally to the stomach as it courses along the

greater curvature of the stomach to the left colic flexure.

The bed of the stomach, on which the stomach rests in

the supine position, is formed by the structures forming the

posterior wall of the omental bursa. From superior to inferior, the bed of the stomach is formed by the left dome of the diaphragm, spleen, left kidney and suprarenal gland, splenic

artery, pancreas, and transverse mesocolon.

Vessels and Nerves of Stomach

The rich arterial supply of the stomach arises from the celiac

trunk and its branches. Most blood is

supplied by anastomoses formed along the lesser curvature

by the right and left gastric arteries, and along the greater

curvature by the right and left gastro-omental (gastro-epiploic) arteries. The fundus and upper body receive

blood from the short and posterior gastric arteries.

The veins of the stomach parallel the arteries in position

and course. The right and left gastric veins

drain into the hepatic portal vein; the short gastric veins

and left gastro-omental veins drain into the splenic vein,

which joins the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) to form the

hepatic portal vein. The right gastro-omental vein empties

in the SMV. A prepyloric vein ascends over the pylorus to

the right gastric vein. Because this vein is obvious in living

persons, surgeons use it for identifying the pylorus.

The gastric lymphatic vessels accompany

the arteries along the greater and lesser curvatures of the

stomach. They drain lymph from its anterior and posterior

surfaces toward its curvatures, where the gastric and gastro-omental lymph nodes are located. The efferent vessels

from these nodes accompany the large arteries to the celiac

lymph nodes. The following is a summary of the lymphatic

drainage of the stomach:

• Lymph from the superior two thirds of the stomach

drains along the right and left gastric vessels to the gastric lymph nodes; lymph from the fundus and superior

part of the body of the stomach also drains along the short

gastric arteries and left gastro-omental vessels to the pancreaticosplenic lymph nodes.

• Lymph from the right two thirds of the inferior third of

the stomach drains along the right gastro-omental vessels

to the pyloric lymph nodes.

• Lymph from the left one third of the greater curvature

drains to the pancreaticoduodenal lymph nodes, which

are located along the short gastric and splenic vessels.

The parasympathetic nerve supply of the stomach is from the anterior and posterior vagal trunks

and their branches, which enter the abdomen through the

esophageal hiatus.

The anterior vagal trunk, derived mainly from the left

vagus nerve (CN X), usually enters the abdomen as a single

branch that lies on the anterior surface of the esophagus. It

runs toward the lesser curvature of the stomach, where it

gives off hepatic and duodenal branches, which leave the

stomach in the hepatoduodenal ligament. The rest of the

anterior vagal trunk continues along the lesser curvature,

giving rise to anterior gastric branches.

The larger posterior vagal trunk, derived mainly from the

right vagus nerve, enters the abdomen on the posterior surface of the esophagus and passes toward the lesser curvature

of the stomach. The posterior vagal trunk supplies branches

to the anterior and posterior surfaces of the stomach. It gives

off a celiac branch, which passes to the celiac plexus, and

then continues along the lesser curvature, giving rise to posterior gastric branches.

The sympathetic nerve supply of the stomach, from the

T6 through T9 segments of the spinal cord, passes to the

celiac plexus through the greater splanchnic nerve and is

distributed through the plexuses around the gastric and gastro-omental arteries.