Main Model

URINARY BLADDER

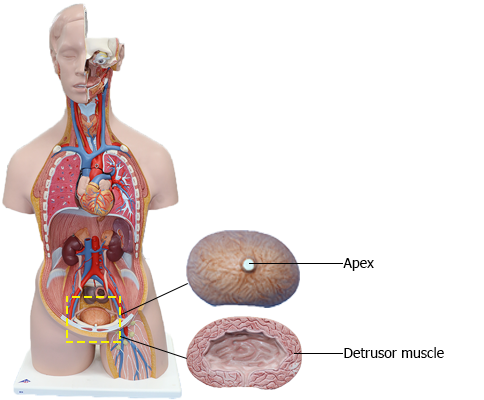

Urinary Bladder

The urinary bladder, a hollow viscus with strong muscular walls, is characterized by its distensibility. The bladder is a temporary reservoir for urine, and varies in size, shape, position, and relationships according to its content, and the state of neighboring viscera. When empty, the adult urinary bladder is located in the lesser pelvis, lying partially superior to and partially posterior to the pubic bones. It is separated from these bones by the potential retropubic space (of Retzius) and lies mostly inferior to the peritoneum, resting on the pubic bones and pubic symphysis anteriorly and the prostate (males) or anterior wall of the vagina (females) posteriorly. The bladder is relatively free within the extraperitoneal subcutaneous fatty tissue, except for its neck, which is held firmly by the lateral ligaments of bladder and the tendinous arch of the pelvic fascia - especially its anterior component, the puboprostatic ligament in males and the pubovesical ligament in females. In females, since the posterior aspect of the bladder rests directly upon the anterior wall of the vagina, the lateral attachment of the vagina to the tendinous arch of the pelvic fascia, the paracolpium, is an indirect but important factor in supporting the urinary bladder.

In infants and young children, the urinary bladder is in the abdomen even when empty. The bladder usually enters the greater pelvis by 6 years of age; however, it is not located entirely within the lesser pelvis until after puberty. An empty bladder in adults lies almost entirely in the lesser pelvis, its superior surface level with the superior margin of the pubic symphysis. As the bladder fills, it enters the greater pelvis as it ascends in the extraperitoneal fatty tissue of the anterior abdominal wall. In some individuals, a full bladder may ascend to the level of the umbilicus.

At the end of micturition (urination), the bladder of a normal adult contains virtually no urine. When empty, the bladder is somewhat tetrahedral and externally has an apex, body, fundus, and neck. The bladder's four surfaces (superior, two inferolateral, and posterior) are most apparent when viewing an empty, contracted bladder that has been removed from a cadaver, when the bladder appears rather boat shaped.

The apex of the bladder points toward the superior edge of the pubic symphysis when the bladder is empty. The fundus of the bladder is opposite the apex, formed by the somewhat convex posterior wall. The body of the bladder is the major portion of the bladder between the apex and the fundus. The fundus and inferolateral surfaces meet inferiorly at the neck of the bladder.

The bladder bed is formed by the structures that directly contact it. On each side, the pubic bones and fascia covering the levator ani and the superior obturator internus lie in contact with the inferolateral surfaces of the bladder. Only the superior surface is covered by peritoneum. Consequently, in males the fundus is separated from the rectum centrally by only the fascial rectovesical septum and laterally by the seminal glands and ampullae of the ductus deferentes. In females the fundus is directly related to the superior anterior wall of the vagina. The bladder is enveloped by a loose connective tissue visceral fascia.

The walls of the bladder are composed chiefly of the detrusor muscle. Toward the neck of the male bladder, the muscle fibers form the involuntary internal urethral sphincter. This sphincter contracts during ejaculation to prevent retrograde ejaculation (ejaculatory reflux) of semen into the bladder. Some fibers run radially and assist in opening the internal urethral orifice. In males, the muscle fibers in the neck of the bladder are continuous with the fibromuscular tissue of the prostate, whereas in females these fibers are continuous with muscle fibers in the wall of the urethra.

The ureteric orifices and the internal urethral orifice are at the angles of the trigone of the bladder. The ureteric orifices are encircled by loops of detrusor musculature that tighten when the bladder contracts to assist in preventing reflux of urine into the ureter. The uvula of the bladder is a slight elevation of the trigone; it is usually more prominent in older men owing to enlargement of the posterior lobe of the prostate.

Arterial Supply and Venous Drainage of Bladder

The main arteries supplying the bladder are branches of the internal iliac arteries. The superior vesical arteries supply anterosuperior parts of the bladder. In males, the inferior vesical arteries supply the fundus and neck of the bladder. In females, the vaginal arteries replace the inferior vesical arteries and send small branches to posteroinferior parts of the bladder. The obturator and inferior gluteal arteries also supply small branches to the bladder.

The veins draining blood from the bladder correspond to the arteries, and are tributaries of the internal iliac veins. In males, the vesical venous plexus is continuous with the prostatic venous plexus, and the combined plexus complex envelops the fundus of the bladder and prostate, the seminal glands, the ductus deferentes, and the inferior ends of the ureters. It also receives blood from the deep dorsal vein of the penis, which drains into the prostatic venous plexus. The vesical venous plexus is the venous network that is most directly associated with the bladder itself. It mainly drains through the inferior vesical veins into the internal iliac veins; however, it may drain through the sacral veins into the internal vertebral venous plexuses. In females, the vesical venous plexus envelops the pelvic part of the urethra and the neck of the bladder, receives blood from the dorsal vein of the clitoris, and communicates with the vaginal or uterovaginal venous plexus.

Innervation of Bladder

Sympathetic fibers are conveyed from inferior thoracic and upper lumbar spinal cord levels to the vesical (pelvic) plexuses primarily through the hypogastric plexuses and nerves, whereas parasympathetic fibers from sacral spinal cord levels are conveyed by the pelvic splanchnic nerves and the inferior hypogastric plexus. The parasympathetic fibers are motor to the detrusor muscle and inhibitory to the internal urethral sphincter of the male bladder. Hence, when visceral afferent fibers are stimulated by stretching, the bladder contracts reflexively, the internal urethral sphincter relaxes (in males), and urine flows into the urethra. With toilet training, we learn to suppress this reflex when we do not wish to void. The sympathetic innervation that stimulates ejaculation simultaneously causes contraction of the internal urethral sphincter, to prevent reflux of semen into the bladder. A sympathetic response at moments other than ejaculation (e.g., self consciousness when standing at the urinal in front of a waiting line) can cause the internal sphincter to contract, hampering the ability to urinate until parasympathetic inhibition of the sphincter occurs.

Sensory fibers from most of the bladder are visceral; reflex afferents follow the course of the parasympathetic fibers, as do those transmitting pain sensations (such as results from overdistension) from the inferior part of the bladder. The superior surface of the bladder is covered with peritoneum and is therefore superior to the pelvic pain line; thus pain fibers from the superior bladder follow the sympathetic fibers retrogradely to the inferior thoracic and upper lumbar spinal ganglia (T11-L2 or L3).