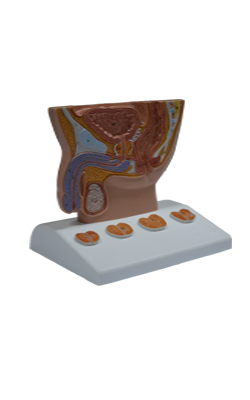

Main Model

Sacral bone

Sacrum

The wedged-shaped sacrum (Latin sacred bone) is usually

composed of five fused sacral vertebrae in adults.

It is located between the hip bones and forms the roof and

posterosuperior wall of the posterior half of the pelvic cavity. The triangular shape of the sacrum results from the

rapid decrease in the size of the inferior lateral masses of

the sacral vertebrae during development. The inferior half

of the sacrum is not weight-bearing; therefore, its bulk is diminished considerably. The sacrum provides strength and

stability to the pelvis and transmits the weight of the body to

the pelvic girdle, the bony ring formed by the hip bones and

sacrum, to which the lower limbs are attached.

The sacral canal is the continuation of the vertebral canal

in the sacrum. It contains the bundle of spinal

nerve roots arising inferior to the L1 vertebra, known as the

cauda equina (Latin horse tail), that descend past the termination of the spinal cord. On the pelvic and posterior surfaces of

the sacrum between its vertebral components are typically four

pairs of sacral foramina for the exit of the posterior and anterior rami of the spinal nerves. The anterior (pelvic) sacral foramina are larger than the posterior (dorsal) ones.

The base of the sacrum is formed by the superior surface of the S1 vertebra. Its superior articular

processes articulate with the inferior articular processes of

the L5 vertebra. The anterior projecting edge of the body

of the S1 vertebra is the sacral promontory (Latin mountain ridge), an important obstetrical landmark.

The apex of the sacrum, its tapering inferior end, has an

oval facet for articulation with the coccyx.

The sacrum supports the vertebral column and forms the

posterior part of the bony pelvis. The sacrum is tilted so that

it articulates with the L5 vertebra at the lumbosacral angle, which varies from 130° to 160°. The sacrum is

often wider in proportion to length in the female than in the male, but the body of the S1 vertebra is usually larger in males.

The pelvic surface of the sacrum is smooth and concave. Four transverse lines on this surface of

sacra from adults indicate where fusion of the sacral vertebrae occurred. During childhood, the individual sacral vertebrae are connected by hyaline cartilage and separated by IV

discs. Fusion of the sacral vertebrae starts after age 20; however, most of the IV discs remain unossified up to or beyond

middle life.

The dorsal surface of the sacrum is rough, convex, and

marked by five prominent longitudinal ridges.

The central ridge, the median sacral crest, represents the

fused rudimentary spinous processes of the superior three

or four sacral vertebra; S5 has no spinous process. The intermediate sacral crests represent the fused articular

processes, and the lateral sacral crests are the tips of the

transverse processes of the fused sacral vertebrae.

The clinically important features of the dorsal surface of

the sacrum are the inverted U-shaped sacral hiatus and the

sacral cornua (Latin horns). The sacral hiatus results from the

absence of the laminae and spinous process of S5 and sometimes S4. The sacral hiatus leads into the sacral canal. Its

depth varies, depending on how much of the spinous process

and laminae of S4 are present. The sacral cornua, representing the inferior articular processes of S5 vertebra, project

inferiorly on each side of the sacral hiatus and are a helpful

guide to its location.

The superior part of the lateral surface of the sacrum

looks somewhat like an auricle (Latin external ear); because

of its shape, this area is called the auricular surface. It is the site of the synovial part of the sacro-iliac

joint between the sacrum and ilium. During life, the auricular surface is covered with hyaline cartilage.