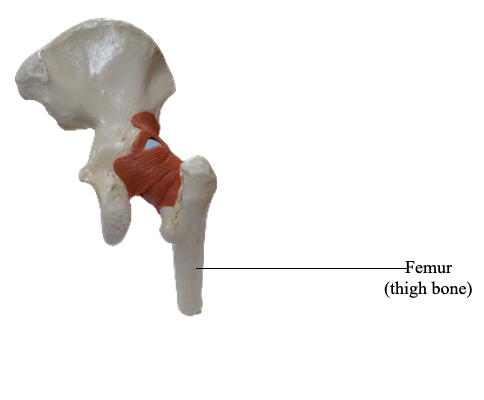

Main Model

Femur (thigh bone)

The femur is the longest and heaviest bone in the body. It transmits body weight from the hip bone to the tibia when a person is standing. Its length is approximately a quarter of the person's height. The femur consists of a shaft (body) and two ends, superior or proximal and inferior or distal.

The superior (proximal) end of the femur consists of a head, neck, and two trochanters (greater and lesser). The round head of the femur makes up two thirds of a sphere that is covered with articular cartilage, except for a medially placed depression or pit, the fovea for the ligament of the head. In early life, the ligament gives passage to an artery supplying the epiphysis of the head. The neck of the femur is trapezoidal, with its narrow end supporting the head and its broader base being continuous with the shaft. Its average diameter is three quarters that of the femoral head.

The proximal femur is “bent” (L-shaped) so that the long axis of the head and neck projects superomedially at an angle to that of the obliquely oriented shaft. This obtuse angle of inclination is greatest (most nearly straight) at birth and gradually diminishes (becomes more acute) until the adult angle is reached (115-140°, averaging 126°).

The angle of inclination is less in females because of the increased width between the acetabula (a consequence of a wider lesser pelvis) and the greater obliquity of the femoral shaft. The angle of inclination allows greater mobility of the femur at the hip joint because it places the head and neck more perpendicular to the acetabulum in the neutral position. The abductors and rotators of the thigh attach mainly to the apex of the angle (the greater trochanter) so they are pulling on a lever (the short limb of the L) that is directed more laterally than vertically. This provides increased leverage for the abductors and rotators of the thigh, and allows the considerable mass of the abductors of the thigh to be placed superior to the femur (in the gluteal region) instead of lateral to it, freeing the lateral aspect of the femoral shaft to provide an increased area for the fleshy attachment of the extensors of the knee.

The angle of inclination also allows the obliquity of the femur within the thigh, which permits the knees to be adjacent and inferior to the trunk. All of this is advantageous for bipedal walking; however, it imposes considerable strain on the neck of the femur. Consequently, fractures of the femoral neck can occur in older people as a result of a slight stumble if the neck has been weakened by osteoporosis (pathologic reduction of bone mass).

The torsion of the proximal lower limb (femur) that occurred during development does not conclude with the long axis of the superior end of the femur (head and neck) parallel to the transverse axis of the inferior end (femoral condyles). When the femur is viewed superiorly (so that one is looking along the long axis of the shaft), it is apparent that the two axes lie at an angle (the torsion angle, or angle of declination), the mean of which is 7° in males and 12° in females. The torsion angle, combined with the angle of inclination, allows rotatory movements of the femoral head within the obliquely placed acetabulum to convert into flexion and extension, abduction and adduction, and rotational movements of the thigh.

Where the femoral neck and shaft join there are two large, blunt elevations called trochanters. The abrupt, conical and rounded lesser trochanter (Greek, a runner) extends medially from the posteromedial part of the junction of the neck and shaft to give tendinous attachment to the primary flexor of the thigh (the iliopsoas).

The greater trochanter is a large, laterally placed bony mass that projects superiorly and posteriorly where the neck joins the femoral shaft, providing attachment and leverage for abductors and rotators of the thigh. The site where the neck and shaft join is indicated by the intertrochanteric line, a roughened ridge formed by the attachment of a powerful ligament (iliofemoral ligament). The intertrochanteric line runs from the greater trochanter and winds around the lesser trochanter to continue posteriorly and inferiorly as a less distinct ridge, the spiral line.

A similar but smoother and more prominent ridge, the intertrochanteric crest, joins the trochanters posteriorly. The rounded elevation on the crest is the quadrate tubercle. In anterior and posterior views, the greater trochanter is in line with the femoral shaft. In posterior and superior views, it overhangs a deep depression medially, the trochanteric fossa.

The shaft of the femur is slightly bowed (convex) anteriorly. This convexity may increase markedly, proceeding laterally as well as anteriorly, if the shaft is weakened by a loss of calcium, as occurs in rickets (a disease attributable to vitamin D deficiency). Most of the shaft is smoothly rounded, providing fleshy origin to extensors of the knee, except posteriorly where a broad, rough line, the linea aspera, provides aponeurotic attachment for adductors of the thigh. This vertical ridge is especially prominent in the middle third of the femoral shaft, where it has medial and lateral lips (margins). Superiorly, the lateral lip blends with the broad, rough gluteal tuberosity, and the medial lip continues as a narrow, rough spiral line.

The spiral line extends toward the lesser trochanter but then passes to the anterior surface of the femur, where it is continuous with the intertrochanteric line. A prominent intermediate ridge, the pectineal line, extends from the central part of the linea aspera to the base of the lesser trochanter. Inferiorly, the linea aspera divides into medial and lateral supracondylar lines, which lead to the medial and lateral femoral condyles.

The medial and lateral femoral condyles make up nearly the entire inferior (distal) end of the femur. The two condyles are on the same horizontal level when the bone is in its anatomical position, so that if an isolated femur is placed upright with both condyles contacting the floor or tabletop, the femoral shaft will assume the same oblique position it occupies in the living body (about 9° from vertical in males and slightly greater in females).

The femoral condyles articulate with menisci (crescentic plates of cartilage) and tibial condyles to form the knee joint. The menisci and tibial condyles glide as a unit across the inferior and posterior aspects of the femoral condyles during flexion and extension. The convexity of the articular surface of the condyles increases as it descends the anterior surface, covering the inferior end, and then ascends posteriorly. The condyles are separated posteriorly and inferiorly by an intercondylar fossa but merge anteriorly, forming a shallow longitudinal depression, the patellar surface, which articulates with the patella. The lateral surface of the lateral condyle has a central projection called the lateral epicondyle. The medial surface of the medial condyle has a larger and more prominent medial epicondyle, superior to which another elevation, the adductor tubercle, forms in relation to a tendon attachment. The epicondyles provide proximal attachment for the medial and lateral collateral ligaments of the knee joint.