Main Model

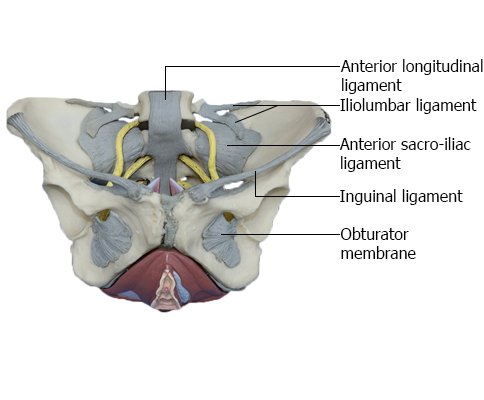

LIGAMENTS OF PELVIC GIRDLE : Ligaments anterior view

Sacro-iliac Joints

The sacro-iliac joints are strong, weight-bearing compound joints, consisting of an anterior synovial joint (between the ear-shaped auricular surfaces of the sacrum and ilium, covered with articular cartilage) and a posterior syndesmosis (between the tuberosities of these bones). The auricular surfaces of this synovial joint have irregular but congruent elevations and depressions that interlock. The sacro-iliac joints differ from most synovial joints in that limited mobility is allowed, a consequence of their role in transmitting the weight of most of the body to the hip bones.

Weight is transferred from the axial skeleton to the ilia via the sacro-iliac ligaments, and then to the femurs during standing, and to the ischial tuberosities during sitting. As long as tight apposition is maintained between the articular surfaces, the sacro-iliac joints remain stable. Unlike a keystone at the top of an arch, the sacrum is actually suspended between the iliac bones and is firmly attached to them by posterior and interosseous sacro-iliac ligaments.

The thin anterior sacro-iliac ligaments are merely the anterior part of the fibrous capsule of the synovial part of the joint. The abundant interosseous sacroiliac ligaments (lying deep between the tuberosities of the sacrum and ilium and occupying an area of approximately 10 cm2) are the primary structures involved in transferring the weight of the upper body from the axial skeleton to the two ilia of the appendicular skeleton.

The posterior sacro-iliac ligaments are the posterior external continuation of the same mass of fibrous tissue. Because the fibers of the interosseous and posterior sacro-iliac ligaments run obliquely upward and outward from the sacrum, the axial weight pushing down on the sacrum actually pulls the ilia inward (medially) so that they compress the sacrum between them, locking the irregular but congruent surfaces of the sacro-iliac joints together. The iliolumbar ligaments are accessory ligaments to this mechanism.

Inferiorly, the posterior sacro-iliac ligaments are joined by fibers extending from the posterior margin of the ilium (between the posterior superior and posterior inferior iliac spines) and the base of the coccyx to form the massive sacrotuberous ligament. This ligament passes from the posterior ilium and lateral sacrum and coccyx to the ischial tuberosity, transforming the sciatic notch of the hip bone into a large sciatic foramen. The sacrospinous ligament, passing from lateral sacrum and coccyx to the ischial spine, further subdivides this foramen into greater and lesser sciatic foramina.

Most of the time, movement at the sacro-iliac joint is limited by interlocking of the articulating bones and the sacro-iliac ligaments to slight gliding and rotary movements. When landing after a high jump or when weightlifting in the standing position, exceptional force is transmitted through the bodies of the lumbar vertebrae to the superior end of the sacrum. Because this transfer of weight occurs anterior to the axis of the sacro-iliac joints, the superior end of the sacrum is pushed inferiorly and anteriorly. However, rotation of the superior sacrum is counterbalanced by the strong sacrotuberous and sacrospinous ligaments that anchor the inferior end of the sacrum to the ischium, preventing its superior and posterior rotation. By allowing only slight upward movement of the inferior end of the sacrum relative to the hip bones, resilience is provided to the sacro-iliac region when the vertebral column sustains sudden increases in force or weight.