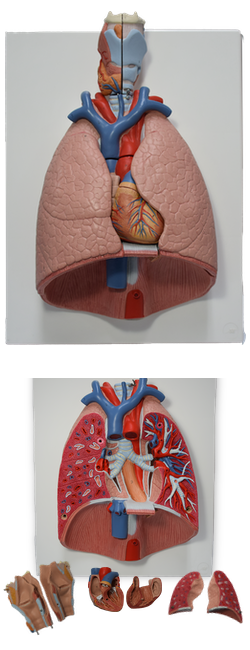

Main Model

G DIAPHRAGM

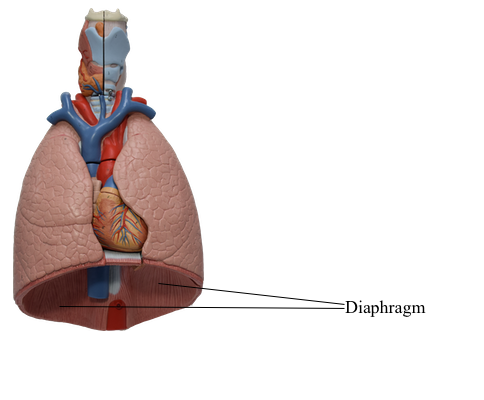

Diaphragm

The diaphragm is a double-domed, musculotendinous

partition separating the thoracic and abdominal cavities. Its

mainly convex superior surface faces the thoracic cavity, and

its concave inferior surface faces the abdominal cavity. The diaphragm is the chief muscle of inspiration (actually, of respiration altogether, because expiration

is largely passive). It descends during inspiration; however,

only its central part moves because its periphery, as the fixed

origin of the muscle, attaches to the inferior margin of the

thoracic cage and the superior lumbar vertebrae.

The pericardium, containing the heart, lies on the central

part of the diaphragm, depressing it slightly. The

diaphragm curves superiorly into right and left domes; normally the right dome is higher than the left dome owing to

the presence of the liver. During expiration, the right dome reaches as high as the 5th rib and the left dome ascends to

the 5th intercostal space. The level of the domes of the diaphragm varies according to the:

• Phase of respiration (inspiration or expiration).

• Posture (e.g., supine or standing).

• Size and degree of distension of the abdominal viscera.

The muscular part of the diaphragm is situated peripherally with fibers that converge radially on the trifoliate central

aponeurotic part, the central tendon. The

central tendon has no bony attachments and is incompletely divided into three leaves, resembling a wide cloverleaf. Although it lies near the center of the diaphragm,

the central tendon is closer to the anterior part of the thorax.

The caval opening (vena caval foramen), through which

the terminal part of the IVC passes to enter the heart, perforates the central tendon. The surrounding muscular part

of the diaphragm forms a continuous sheet; however, for

descriptive purposes it is divided into three parts, based on

the peripheral attachments:

• Sternal part: consisting of two muscular slips that attach

to the posterior aspect of the xiphoid process; this part is

not always present.

• Costal part: consisting of wide muscular slips that attach

to the internal surfaces of the inferior six costal cartilages

and their adjoining ribs on each side; the costal parts form

the right and left domes.

• Lumbar part: arising from two aponeurotic arches, the

medial and lateral arcuate ligaments, and the three superior lumbar vertebrae; the lumbar part forms right and left

muscular crura that ascend to the central tendon.

The crura of the diaphragm are musculotendinous bands

that arise from the anterior surfaces of the bodies of the

superior three lumbar vertebrae, the anterior longitudinal

ligament, and the IV discs. The right crus, larger and longer

than the left crus, arises from the first three or four lumbar

vertebrae. The left crus arises from the first two or three

lumbar vertebrae. Because it lies to the left of the midline, it

is surprising to find that the esophageal hiatus is a formation in the right crus; however, if the muscular fibers bounding

each side of the hiatus are traced inferiorly, it will be seen

that they pass to the right of the aortic hiatus.

The right and left crura and the fibrous median arcuate ligament, which unites them as it arches over the anterior aspect of

the aorta, form the aortic hiatus. The diaphragm is also attached

on each side to the medial and lateral arcuate ligaments. The

medial arcuate ligament is a thickening of the fascia covering

the psoas major, spanning between the lumbar vertebral bodies

and the tip of the transverse process of L1. The lateral arcuate

ligament covers the quadratus lumborum muscles, continuing

from the L12 transverse process to the tip of the 12th rib.

The superior aspect of the central tendon of the diaphragm

is fused with the inferior surface of the fibrous pericardium,

the strong, external part of the fibroserous pericardial sac

that encloses the heart.

Vessels and Nerves of Diaphragm

The arteries of the diaphragm form a branch-like pattern on

both its superior (thoracic) and inferior (abdominal) surfaces.

The arteries supplying the superior surface of the diaphragm are the pericardiacophrenic and musculophrenic arteries, branches of the internal thoracic artery, and the superior phrenic arteries, arising from the thoracic aorta. The arteries supplying the inferior surface of the

diaphragm are the inferior phrenic arteries, which typically are the first branches of the abdominal aorta; however,

they may arise from the celiac trunk.

The veins draining the superior surface of the diaphragm

are the pericardiacophrenic and musculophrenic veins,

which empty into the internal thoracic veins and, on the right

side, a superior phrenic vein, which drains into the IVC.

Some veins from the posterior curvature of the diaphragm

drain into the azygos and hemi-azygos veins.

The veins draining the inferior surface of the diaphragm are

the inferior phrenic veins. The right inferior phrenic vein

usually opens into the IVC, whereas the left inferior phrenic

vein is usually double, with one branch passing anterior to

the esophageal hiatus to end in the IVC and the other, more

posterior branch usually joining the left suprarenal vein. The

right and left phrenic veins may anastomose with each other.

The lymphatic plexuses on the superior and inferior surfaces of the diaphragm communicate freely. The

anterior and posterior diaphragmatic lymph nodes are

on the superior surface of the diaphragm. Lymph from these

nodes drains into the parasternal, posterior mediastinal, and phrenic lymph nodes. Lymphatic vessels from the inferior

surface of the diaphragm drain into the anterior diaphragmatic, phrenic, and superior lumbar (caval/aortic) lymph

nodes. Lymphatic capillaries are dense on the inferior surface of the diaphragm, constituting the primary means for

absorption of peritoneal fluid and substances introduced by

intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection.

The entire motor supply to the diaphragm is from the

right and left phrenic nerves, each of which arises from the

anterior rami of C3-C5 segments of the spinal cord and is

distributed to the ipsilateral half of the diaphragm from its inferior surface. Sensory innervation (pain and proprioception) to the diaphragm is also mostly from the

phrenic nerves. Peripheral parts of the diaphragm receive

their sensory nerve supply from the intercostal nerves (lower

six or seven) and the subcostal nerves.

Diaphragmatic Apertures

The diaphragmatic apertures (openings, hiatus) permit

structures (vessels, nerves, and lymphatics) to pass between

the thorax and abdomen. There

are three large apertures for the IVC, esophagus, and aorta

and a number of small ones.

Caval Opening

The caval opening is an aperture in the central tendon primarily for the IVC. Also passing through the caval opening

are terminal branches of the right phrenic nerve and a few

lymphatic vessels on their way from the liver to the middle

phrenic and mediastinal lymph nodes. The caval opening is

located to the right of the median plane at the junction of the

central tendon's right and middle leaves. The most superior

of the three large diaphragmatic apertures, the caval opening

lies at the level of the IV disc between the T8 and T9 vertebrae. The IVC is adherent to the margin of the opening; consequently, when the diaphragm contracts during inspiration, it widens the opening and dilates the IVC. These changes

facilitate blood flow through this large vein to the heart.

Esophageal Hiatus

The esophageal hiatus is an oval opening for the esophagus in the muscle of the right crus of the diaphragm at the

level of the T10 vertebra. The esophageal hiatus also transmits

the anterior and posterior vagal trunks, esophageal branches

of the left gastric vessels, and a few lymphatic vessels. The

fibers of the right crus of the diaphragm decussate (cross one

another) inferior to the hiatus, forming a muscular sphincter

for the esophagus that constricts it when the diaphragm contracts. The esophageal hiatus is superior to and to the left of

the aortic hiatus. In most individuals (70%), both margins of

the hiatus are formed by muscular bundles of the right crus. In

others (30%), a superficial muscular bundle from the left crus

contributes to the formation of the right margin of the hiatus.

Aortic Hiatus

The aortic hiatus is the opening posterior in the diaphragm

for the descending aorta. Because the aorta does not pierce the

diaphragm, movements of the diaphragm do not affect blood

flow through the aorta during respiration. The aorta passes

between the crura of the diaphragm posterior to the median

arcuate ligament, which is at the level of the inferior border of

the T12 vertebra. The aortic hiatus also transmits the thoracic

duct and sometimes the azygos and hemi-azygos veins.

Small Openings in Diaphragm

In addition to the three main apertures, there is a small opening, the sternocostal triangle (foramen), between the sternal and costal attachments of the diaphragm. This triangle transmits lymphatic vessels from the diaphragmatic surface of

the liver and the superior epigastric vessels. The sympathetic

trunks pass deep to the medial arcuate ligament, accompanied by the least splanchnic nerves. There are two small apertures in each crus of the diaphragm; one transmits the greater

splanchnic nerve and the other the lesser splanchnic nerve.

Actions of Diaphragm

When the diaphragm contracts, its domes are pulled inferiorly

so that the convexity of the diaphragm is somewhat flattened.

Although this movement is often described as the "descent of

the diaphragm," only the domes of the diaphragm descend.

The diaphragm's periphery remains attached to the ribs and

cartilages of the inferior six ribs. As the diaphragm descends, it pushes the abdominal viscera inferiorly. This increases the

volume of the thoracic cavity and decreases the intrathoracic

pressure, resulting in air being taken into the lungs. In addition, the volume of the abdominal cavity decreases slightly

and intra-abdominal pressure increases somewhat.

Movements of the diaphragm are also important in circulation

because the increased intra-abdominal pressure and decreased

intrathoracic pressure help return venous blood to the heart.

When the diaphragm contracts, compressing the abdominal viscera, blood in the IVC is forced superiorly into the heart.

The diaphragm is at its most superior level when a person

is supine (with the upper body lowered, the Trendelenburg

position). In this position, the abdominal viscera push the diaphragm superiorly in the thoracic cavity. When a person

lies on one side, the hemidiaphragm rises to a more superior

level because of the greater push of the viscera on that side.

Conversely, the diaphragm assumes an inferior level when

a person is sitting or standing. For this reason, people with

dyspnea (difficult breathing) prefer to sit up, not lie down;

non-tidal (reserve) lung volume is increased, and the diaphragm is working with gravity rather than opposing it.