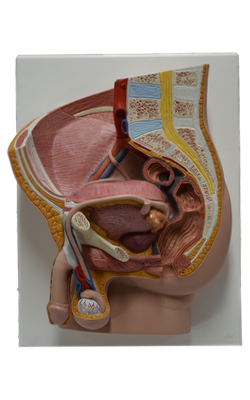

Main Model

Visceral peritoneum

The peritoneum is a continuous, glistening, and slippery transparent serous membrane. It lines the abdominopelvic cavity and invests the viscera. The peritoneum consists of two continuous layers: the parietal peritoneum, which lines the internal surface of the abdominopelvic wall, and the visceral peritoneum, which invests viscera such as the stomach and intestines. Both layers of peritoneum consist of mesothelium, a layer of simple squamous epithelial cells.

The parietal peritoneum is served by the same blood and lymphatic vasculature and the same somatic nerve supply, as is the region of the wall it lines. Like the overlying skin, the peritoneum lining the interior of the body wall is sensitive to pressure, pain, heat and cold, and laceration. Pain from the parietal peritoneum is generally well localized, except for that on the inferior surface of the central part of the diaphragm, where innervation is provided by the phrenic nerves; irritation here is often referred to the C3-C5 dermatomes over the shoulder.

The visceral peritoneum and the organs it covers are served by the same blood and lymphatic vasculature and visceral nerve supply. The visceral peritoneum is insensitive to touch, heat and cold, and laceration; it is stimulated primarily by stretching and chemical irritation. The pain produced is poorly localized, being referred to the dermatomes of the spinal ganglia providing the sensory fibers, particularly to midline portions of these dermatomes. Consequently, pain from foregut derivatives is usually experienced in the epigastric region, that from midgut derivatives in the umbilical region, and that from hindgut derivatives in the pubic region.

The peritoneum and viscera are in the abdominopelvic cavity. The relationship of the viscera to the peritoneum is as follows:

• Intraperitoneal organs are almost completely covered with visceral peritoneum (e.g., the stomach and spleen). Intraperitoneal in this case does not mean inside the peritoneal cavity (although the term is used clinically for substances injected into this cavity). Intraperitoneal organs have conceptually, if not literally, invaginated into the closed sac, like pressing your fist into an inflated balloon.

• Extraperitoneal, retroperitoneal, and subperitoneal organs are also outside the peritoneal cavity - external to the parietal peritoneum - and are only partially covered with peritoneum (usually on just one surface). Retroperitoneal organs such as the kidneys are between the parietal peritoneum and the posterior abdominal wall and have parietal peritoneum only on their anterior surfaces (often with a variable amount of intervening fat). Similarly, the subperitoneal urinary bladder has parietal peritoneum only on its superior surface.

The peritoneal cavity is within the abdominal cavity and continues inferiorly into the pelvic cavity. The peritoneal cavity is a potential space of capillary thinness between the parietal and visceral layers of peritoneum. It contains no organs but contains a thin film of peritoneal fluid, which is composed of water, electrolytes, and other substances derived from interstitial fluid in adjacent tissues. Peritoneal fluid lubricates the peritoneal surfaces, enabling the viscera to move over each other without friction, and allowing the movements of digestion. In addition to lubricating the surfaces of the viscera, the peritoneal fluid contains leukocytes and antibodies that resist infection. Lymphatic vessels, particularly on the inferior surface of the constantly active diaphragm, absorb the peritoneal fluid. The peritoneal cavity is completely closed in males. However, there is a communication pathway in females to the exterior of the body through the uterine tubes, uterine cavity, and vagina. This communication constitutes a potential pathway of infection from the exterior.