Main Model

LIVER : Liver (2)

Liver

The liver is the largest gland in the body and, after the skin, the largest single organ. It weighs approximately 1500 g and accounts for approximately 2.5% of adult body weight. In a mature fetus - when it serves as a hematopoietic organ - it is proportionately twice as large (5% of body weight).

Except for fat, all nutrients absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract are initially conveyed to the liver by the portal venous system. In addition to its many metabolic activities, the liver stores glycogen and secretes bile, a yellow-brown or green fluid that aids in the emulsification of fat.

Bile passes from the liver via the biliary ducts - right and left hepatic ducts - that join to form the common hepatic duct, which unites with the cystic duct to form the (common) bile duct. The liver produces bile continuously; however, between meals it accumulates and is stored in the gallbladder, which also concentrates the bile by absorbing water and salts. When food arrives in the duodenum, the gallbladder sends concentrated bile through the biliary ducts to the duodenum.

Surface Anatomy, Surfaces, Peritoneal Reflections, and Relationships of Liver

The liver lies mainly in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, where it is protected by the thoracic (rib) cage and the diaphragm. The normal liver lies deep to ribs 7-11 on the right side and crosses the midline toward the left nipple. The liver occupies most of the right hypochondrium and upper epigastrium and extends into the left hypochondrium. The liver moves with the excursions of the diaphragm and is located more inferiorly when one is erect because of gravity. This mobility facilitates palpation.

The liver has a convex diaphragmatic surface (anterior, superior, and some posterior) and a relatively flat or even concave visceral surface (postero-inferior), which are separated anteriorly by its sharp inferior border that follows the right costal margin inferior to the diaphragm.

The diaphragmatic surface of the liver is smooth and dome shaped, where it is related to the concavity of the inferior surface of the diaphragm, which separates it from the pleurae, lungs, pericardium, and heart. Subphrenic recesses - superior extensions of the peritoneal cavity (greater sac) - exist between diaphragm and the anterior and superior aspects of the diaphragmatic surface of the liver. The subphrenic recesses are separated into right and left recesses by the falciform ligament, which extends between the liver and the anterior abdominal wall. The portion of the supracolic compartment of the peritoneal cavity immediately inferior to the liver is the subhepatic space.

The hepatorenal recess (hepatorenal pouch; Morison pouch) is the posterosuperior extension of the subhepatic space, lying between the right part of the visceral surface of the liver and the right kidney and suprarenal gland. The hepatorenal recess is a gravity-dependent part of the peritoneal cavity in the supine position; fluid draining from the omental bursa flows into this recess. The hepatorenal recess communicates anteriorly with the right subphrenic recess. Recall that normally all recesses of the peritoneal cavity are potential spaces only, containing just enough peritoneal fluid to lubricate the adjacent peritoneal membranes.

The diaphragmatic surface of the liver is covered with visceral peritoneum, except posteriorly in the bare area of the liver, where it lies in direct contact with the diaphragm. The bare area is demarcated by the reflection of peritoneum from the diaphragm to it as the anterior (upper) and posterior (lower) layers of the coronary ligament. These layers meet on the right to form the right triangular ligament and diverge toward the left to enclose the triangular bare area. The anterior layer of the coronary ligament is continuous on the left with the right layer of the falciform ligament, and the posterior layer is continuous with the right layer of the lesser omentum. Near the apex (the left extremity) of the wedge-shaped liver, the anterior and posterior layers of the left part of the coronary ligament meet to form the left triangular ligament. The IVC traverses a deep groove for the vena cava within the bare area of the liver.

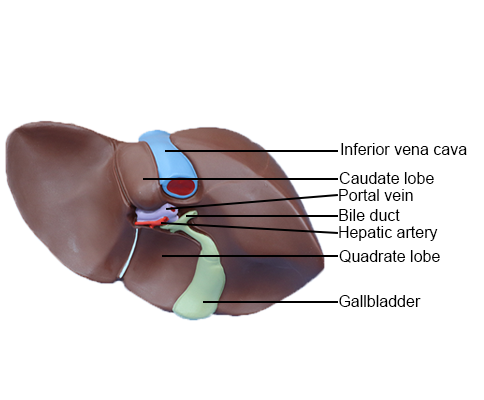

The visceral surface of the liver is also covered with visceral peritoneum, except in the fossa for the gallbladder and the porta hepatis - a transverse fissure where the vessels (hepatic portal vein, hepatic artery, and lymphatic vessels), the hepatic nerve plexus, and hepatic ducts that supply and drain the liver enter and leave it. In contrast to the smooth diaphragmatic surface, the visceral surface bears multiple fissures and impressions from contact with other organs.

Two sagittally oriented fissures, linked centrally by the transverse porta hepatis, form the letter H on the visceral surface. The right sagittal fissure is the continuous groove formed anteriorly by the fossa for the gallbladder and posteriorly by the groove for the vena cava. The umbilical (left sagittal) fissure is the continuous groove formed anteriorly by the fissure for the round ligament and posteriorly by the fissure for the ligamentum venosum. The round ligament of the liver (Latin ligamentum teres hepatis) is the fibrous remnant of the umbilical vein, which carried well-oxygenated and nutrient-rich blood from the placenta to the fetus. The round ligament and small para-umbilical veins course in the free edge of the falciform ligament. The ligamentum venosum is the fibrous remnant of the fetal ductus venosus, which shunted blood from the umbilical vein to the IVC, short-circuiting the liver.

The lesser omentum, enclosing the portal triad (bile duct, hepatic artery, and hepatic portal vein) passes from the liver to the lesser curvature of the stomach and the first 2 cm of the superior part of the duodenum. The thick, free edge of the lesser omentum extends between the porta hepatis and the duodenum (the hepatoduodenal ligament) and encloses the structures that pass through the porta hepatis. The sheet-like remainder of the lesser omentum, the hepatogastric ligament, extends between the groove for the ligamentum venosum and the lesser curvature of the stomach.

In addition to the fissures, impressions on (areas of) the visceral surface reflect the liver's relationship to the:

• Right side of the anterior aspect of the stomach (gastric and pyloric areas).

• Superior part of the duodenum (duodenal area).

• Lesser omentum (extends into the fissure for the ligamentum venosum).

• Gallbladder (fossa for gallbladder).

• Right colic flexure and right transverse colon (colic area).

• Right kidney and suprarenal gland (renal and suprarenal areas).

Anatomical Lobes of Liver

Externally, the liver is divided into two anatomical lobes and two accessory lobes by the reflections of peritoneum from its surface, the fissures formed in relation to those reflections and the vessels serving the liver and the gallbladder. These superficial "lobes" are not true lobes as the term is generally used in relation to glands and are only secondarily related to the liver's internal architecture. The essentially midline plane defined by the attachment of the falciform ligament and the left sagittal fissure separates a large right lobe from a much smaller left lobe. On the slanted visceral surface, the right and left sagittal fissures course on each side of - and the transverse porta hepatis separates - two accessory lobes (parts of the anatomic right lobe): the quadrate lobe anteriorly and inferiorly and the caudate lobe posteriorly and superiorly. The caudate lobe was so-named not because it is caudal in position (it is not) but because it often gives rise to a "tail" in the form of an elongated papillary process. A caudate process extends to the right, between the IVC and the porta hepatis, connecting the caudate and right lobes.

Functional Subdivision of Liver

Although not distinctly demarcated internally, where the parenchyma appears continuous, the liver has functionally independent right and left livers (parts or portal lobes) that are much more equal in size than the anatomical lobes; however, the right liver is still somewhat larger. Each part receives its own primary branch of the hepatic artery and hepatic portal vein and is drained by its own hepatic duct. The caudate lobe may in fact be considered a third liver; its vascularization is independent of the bifurcation of the portal triad (it receives vessels from both bundles) and is drained by one or two small hepatic veins, which enter directly into the IVC distal to the main hepatic veins. The liver can be further subdivided into four divisions and then into eight surgically resectable hepatic segments, each served independently by a secondary or tertiary branch of the portal triad, respectively.

Hepatic (Surgical) Segments of Liver

Except for the caudate lobe (segment I), the liver is divided into right and left livers based on the primary (1°) division of the portal triad into right and left branches, the plane between the right and the left livers being the main portal fissure in which the middle hepatic vein lies. On the visceral surface, this plane is demarcated by the right sagittal fissure. The plane is demarcated on the diaphragmatic surface by extrapolating an imaginary line - the Cantlie line - from the notch for the fundus of the gallbladder to the IVC. The right and left livers are subdivided vertically into medial and lateral divisions by the right portal and umbilical fissures, in which the right and left hepatic veins lie. The right portal fissure has no external demarcation. Each of the four divisions receives a secondary (2°) branch of the portal triad. (Note: the medial division of the left liver - left medial division - is part of the right anatomical lobe; the left lateral division is the same as the left anatomical lobe.) A transverse hepatic plane at the level of the horizontal parts of the right and left branches of the portal triad subdivides three of the four divisions (all but the left medial division), creating six hepatic segments, each receiving tertiary branches of the triad. The left medial division is also counted as a hepatic segment, so that the main part of the liver has seven segments (segments II-VIII, numbered clockwise), which have also been given a descriptive name. The caudate lobe (segment I, bringing the total number of segments to eight) is supplied by branches of both divisions and is drained by its own minor hepatic veins.

While the pattern of segmentation described here is the most common pattern, the segments vary considerably in size and shape as a result of individual variation in the branching of the hepatic and portal vessels.

Blood Vessels of Liver

The liver, like the lungs, has a dual blood supply (afferent vessels): a dominant venous source and a lesser arterial one. The hepatic portal vein brings 75-80% of the blood to the liver. Portal blood, containing about 40% more oxygen than blood returning to the heart from the systemic circuit, sustains the liver parenchyma (liver cells or hepatocytes). The hepatic portal vein carries virtually all of the nutrients absorbed by the alimentary tract to the sinusoids of the liver. The exception is lipids, which are absorbed into and bypass the liver via the lymphatic system. Arterial blood from the hepatic artery, accounting for only 20-25% of blood received by the liver, is distributed initially to non-parenchymal structures, particularly the intrahepatic bile ducts.

The hepatic portal vein, a short, wide vein, is formed by the superior mesenteric and splenic veins posterior to the neck of the pancreas. It ascends anterior to the IVC as part of the portal triad in the hepatoduodenal ligament. The hepatic artery, a branch of the celiac trunk, may be divided into the common hepatic artery, from the celiac trunk to the origin of the gastroduodenal artery, and the hepatic artery proper, from the origin of the gastroduodenal artery to the bifurcation of the hepatic artery. At or close to the porta hepatis, the hepatic artery and hepatic portal vein terminate by dividing into right and left branches; these primary branches supply the right and left livers, respectively. Within the right and left livers, the simultaneous secondary branchings of the hepatic portal vein and hepatic artery supply the medial and lateral divisions of the right and left liver, with three of the four secondary branches undergoing further (tertiary) branchings to supply independently seven of the eight hepatic segments.

Between the divisions are the right, intermediate (middle), and left hepatic veins, which are intersegmental in their distribution and function, draining parts of adjacent segments. The hepatic veins, formed by the union of collecting veins that in turn drain the central veins of the hepatic parenchyma, open into the IVC just inferior to the diaphragm. The attachment of these veins to the IVC helps hold the liver in position.

Lymphatic Drainage and Innervation of Liver

The liver is a major lymph-producing organ. Between one quarter and one half of the lymph entering the thoracic duct comes from the liver.

The lymphatic vessels of the liver occur as superficial lymphatics in the subperitoneal fibrous capsule of the liver (Glisson capsule), which forms its outer surface, and as deep lymphatics in the connective tissue, which accompany the ramifications of the portal triad and hepatic veins. Most lymph is formed in the perisinusoidal spaces (of Disse) and drains to the deep lymphatics in the surrounding intralobular portal triads.

Superficial lymphatics from the anterior aspects of the diaphragmatic and visceral surfaces of the liver, and deep lymphatic vessels accompanying the portal triads, converge toward the porta hepatis. The superficial lymphatics drain to the hepatic lymph nodes scattered along the hepatic vessels and ducts in the lesser omentum. Efferent lymphatic vessels from the hepatic nodes drain into celiac lymph nodes, which in turn drain into the cisterna chyli (chyle cistern), a dilated sac at the inferior end of the thoracic duct.

Superficial lymphatics from the posterior aspects of the diaphragmatic and visceral surfaces of the liver drain toward the bare area of the liver. Here they drain into phrenic lymph nodes, or join deep lymphatics that have accompanied the hepatic veins converging on the IVC, and pass with this large vein through the diaphragm to drain into the posterior mediastinal lymph nodes. Efferent lymphatic vessels from these nodes join the right lymphatic and thoracic ducts. A few lymphatic vessels follow different routes:

• From the posterior surface of the left lobe of the liver toward the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm to end in the left gastric lymph nodes.

• From the anterior central diaphragmatic surface along the falciform ligament to the parasternal lymph nodes.

• Along the round ligament of the liver to the umbilicus and lymphatics of the anterior abdominal wall.

The nerves of the liver are derived from the hepatic plexus, the largest derivative of the celiac plexus. The hepatic plexus accompanies the branches of the hepatic artery and hepatic portal vein to the liver. This plexus consists of sympathetic fibers from the celiac plexus and parasympathetic fibers from the anterior and posterior vagal trunks. Nerve fibers accompany the vessels and biliary ducts of the portal triad. Other than vasoconstriction, their function is unclear.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Gallbladder

The gallbladder (7-10 cm long) lies in the fossa for the gallbladder on the visceral surface of the liver. This shallow fossa lies at the junction of the right and left (parts of the) liver.

The relationship of the gallbladder to the duodenum is so intimate that the superior part of the duodenum is usually stained with bile in the cadaver. Because the liver and gallbladder must be retracted superiorly to expose the gallbladder during an open anterior surgical approach (and atlases often depict it in this position), it is easy to forget that, in its natural position, the body of the gallbladder lies anterior to the superior part of the duodenum, and its neck and cystic duct are immediately superior to the duodenum.

The pear-shaped gallbladder can hold up to 50 mL of bile. Peritoneum completely surrounds the fundus of the gallbladder and binds its body and neck to the liver. The hepatic surface of the gallbladder attaches to the liver by connective tissue of the fibrous capsule of the liver.

The gallbladder has three parts, the:

• Fundus: the wide blunt end that usually projects from the inferior border of the liver at the tip of the right 9th costal cartilage in the midclavicular line (MCL).

• Body: main portion that contacts the visceral surface of the liver, transverse colon, and superior part of the duodenum.

• Neck: narrow, tapering end, opposite the fundus and directed toward the porta hepatis; it typically makes an S-shaped bend and joins the cystic duct.

The cystic duct (3-4 cm long) connects the neck of the gallbladder to the common hepatic duct. The mucosa of the neck spirals into the spiral fold (spiral valve). The spiral fold helps keep the cystic duct open; thus bile can easily be diverted into the gallbladder when the distal end of the bile duct is closed by the sphincter of the bile duct and/or hepatopancreatic sphincter, or bile can pass to the duodenum as the gallbladder contracts. The spiral fold also offers additional resistance to sudden dumping of bile when the sphincters are closed, and intra-abdominal pressure is suddenly increased, as during a sneeze or cough. The cystic duct passes between the layers of the lesser omentum, usually parallel to the common hepatic duct, which it joins to form the bile duct.

The arterial supply of the gallbladder and cystic duct is from the cystic artery. The cystic artery commonly arises from the right hepatic artery in the triangle between the common hepatic duct, cystic duct, and visceral surface of the liver, the cystohepatic triangle (of Calot). Variations occur in the origin and course of the cystic artery.

The venous drainage from the neck of the gallbladder and cystic duct flows via the cystic veins. These small and usually multiple veins enter the liver directly or drain through the hepatic portal vein to the liver, after joining the veins draining the hepatic ducts and proximal bile duct. The veins from the fundus and body of the gallbladder pass directly into the visceral surface of the liver and drain into the hepatic sinusoids. Because this is drainage from one capillary (sinusoidal) bed to another, it constitutes an additional (parallel) portal system.

The lymphatic drainage of the gallbladder is to the hepatic lymph nodes, often through cystic lymph nodes located near the neck of the gallbladder. Efferent lymphatic vessels from these nodes pass to the celiac lymph nodes.

The nerves to the gallbladder and cystic duct pass along the cystic artery from the celiac (nerve) plexus (sympathetic and visceral afferent [pain] fibers), the vagus nerve (parasympathetic), and the right phrenic nerve (actually somatic afferent fibers). Parasympathetic stimulation causes contractions of the gallbladder and relaxation of the sphincters at the hepatopancreatic ampulla. However, these responses are generally stimulated by the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK), produced by the duodenal walls (in response to the arrival of a fatty meal), and circulated through the bloodstream.