Main Model

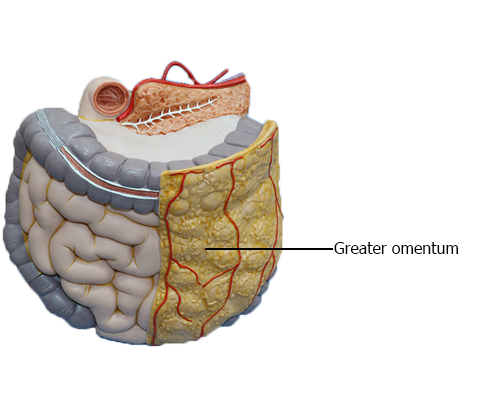

LARGE INTESTINE : Greater omentum

Peritoneal Formations

The peritoneal cavity has a complex shape. Some of the facts

relating to this include the following:

• The peritoneal cavity houses a great length of gut, most of

which is covered with peritoneum.

• Extensive continuities are required between the parietal

and visceral peritoneum to convey the necessary neurovascular structures from the body wall to the viscera.

• Although the volume of the abdominal cavity is a fraction

of the body's volume, the parietal and visceral peritoneum

lining the peritoneal cavity within it have a much greater

surface area than the body's outer surface (skin); therefore, the peritoneum is highly convoluted.

Various terms are used to describe the parts of the peritoneum that connect organs with other organs, or to the

abdominal wall, and the compartments and recesses that are

formed as a consequence.

A mesentery is a double layer of peritoneum that occurs

as a result of the invagination of the peritoneum by an organ

and constitutes a continuity of the visceral and parietal peritoneum. It provides a means for neurovascular communications between the organ and the body wall.

A mesentery connects an intraperitoneal organ to the body

wall - usually the posterior abdominal wall (e.g., mesentery of

the small intestine).

The small intestine mesentery is usually referred to

simply as "the mesentery"; however, mesenteries related to

other specific parts of the alimentary tract are named accordingly - for example, the transverse and sigmoid mesocolons, mesoesophagus, mesogastrium, and mesoappendix. Mesenteries have a core of connective tissue containing blood and lymphatic vessels, nerves, lymph nodes,

and fat.

An omentum is a double-layered extension or fold of peritoneum that passes from the stomach and proximal part of the

duodenum to adjacent organs in the abdominal cavity.

• The greater omentum is a prominent, four-layered

peritoneal fold that hangs down like an apron from the

greater curvature of the stomach and the proximal part

of the duodenum. After descending,

it folds back and attaches to the anterior surface of the

transverse colon and its mesentery.

• The lesser omentum is a much smaller, double-layered

peritoneal fold that connects the lesser curvature of the

stomach and the proximal part of the duodenum to the

liver. It also connects the stomach to a

triad of structures that run between the duodenum and

liver in the free edge of the lesser omentum.

A peritoneal ligament consists of a double layer of peritoneum that connects an organ with another organ or to the

abdominal wall.

The liver is connected to the:

• Anterior abdominal wall by the falciform ligament.

• Stomach by the hepatogastric ligament, the membranous portion of the lesser omentum.

• Duodenum by the hepatoduodenal ligament, the

thickened free edge of the lesser omentum, which conducts the portal triad: portal vein, hepatic artery, and bile

duct.

The hepatogastric and hepatoduodenal ligaments are continuous parts of the lesser omentum and are separated only

for descriptive convenience.

The stomach is connected to the:

• Inferior surface of the diaphragm by the gastrophrenic

ligament.

• Spleen by the gastrosplenic ligament, which reflects to

the hilum of the spleen.

• Transverse colon by the gastrocolic ligament, the

apron-like part of the greater omentum, which descends

from the greater curvature, turns under, and then ascends

to the transverse colon.

All these structures have a continuous attachment along

the greater curvature of the stomach, and are all part of the

greater omentum, separated only for descriptive purposes.

Although intraperitoneal organs may be almost entirely

covered with visceral peritoneum, every organ must have

an area that is not covered to allow the entrance or exit

of neurovascular structures. Such areas are called bare

areas, formed in relation to the attachments of the peritoneal formations to the organs, including mesenteries, omenta, and ligaments that convey the neurovascular

structures.

A peritoneal fold is a reflection of peritoneum that is

raised from the body wall by underlying blood vessels, ducts,

and ligaments formed by obliterated fetal vessels (e.g., the

umbilical folds on the internal surface of the anterolateral

abdominal wall). Some peritoneal folds contain blood vessels and bleed if cut, such as the lateral umbilical

folds, which contain the inferior epigastric arteries.

A peritoneal recess, or fossa, is a pouch of peritoneum

that is formed by a peritoneal fold (e.g., the inferior recess of

the omental bursa between the layers of the greater omentum, and the supravesical and umbilical fossae between the

umbilical folds).

Subdivisions of Peritoneal Cavity

After the rotation and development of the greater curvature

of the stomach during development, the

peritoneal cavity is divided into the greater and lesser peritoneal

sacs. The greater sac is the main and larger part of

the peritoneal cavity. A surgical incision through the anterolateral abdominal wall enters the greater sac. The omental bursa

(lesser sac) lies posterior to the stomach and lesser omentum.

The transverse mesocolon (mesentery of the transverse

colon) divides the abdominal cavity into a supracolic compartment, containing the stomach, liver, and spleen, and an

infracolic compartment, containing the small intestine and

ascending and descending colon. The infracolic compartment

lies posterior to the greater omentum and is divided into right and left infracolic spaces by the mesentery of the small intestine. Free communication occurs between the supracolic and the infracolic compartments through the paracolic

gutters, the grooves between the lateral aspect of the ascending

or descending colon and the posterolateral abdominal wall.

The omental bursa is an extensive sac-like cavity that

lies posterior to the stomach, lesser omentum, and adjacent

structures. The omental bursa

has a superior recess, limited superiorly by the diaphragm

and the posterior layers of the coronary ligament of the liver,

and an inferior recess between the superior parts of the layers

of the greater omentum.

The omental bursa permits free movement of the stomach on the structures posterior and inferior to it because

the anterior and posterior walls of the omental bursa slide

smoothly over each other. Most of the inferior recess of the

bursa becomes sealed off from the main part posterior to the

stomach after adhesion of the anterior and posterior layers of

the greater omentum.

The omental bursa communicates with the greater sac

through the omental foramen (epiploic foramen), an opening situated posterior to the free edge of the lesser omentum (hepatoduodenal ligament). The omental foramen can be

located by running a finger along the gallbladder to the free edge

of the lesser omentum. The omental foramen usually

admits two fingers. The boundaries of the omental foramen are

• Anteriorly: the hepatoduodenal ligament (free edge

of lesser omentum), containing the hepatic portal vein,

hepatic artery, and bile duct.

• Posteriorly: the IVC and a muscular band, the right crus

of the diaphragm, covered anteriorly with parietal peritoneum. (They are retroperitoneal.)

• Superiorly: the liver, covered with visceral peritoneum.

• Inferiorly: the superior or first part of the duodenum.