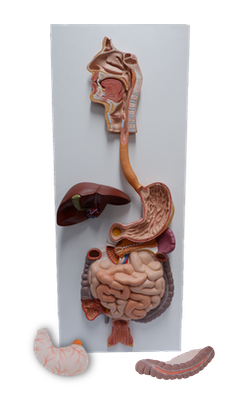

Main Model

Gallbladder

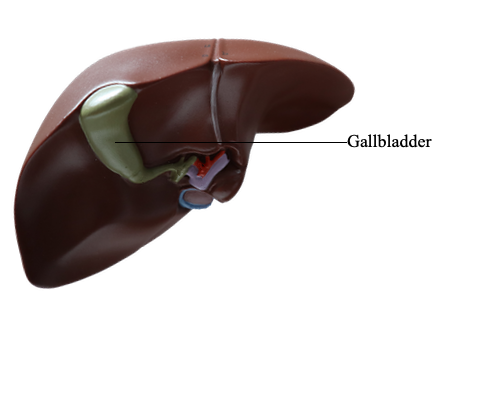

Gallbladder

The gallbladder (7-10 cm long) lies in the fossa for the gallbladder on the visceral surface of the liver. This shallow fossa lies at the junction of the right and left (parts of the) liver.

The relationship of the gallbladder to the duodenum is so intimate that the superior part of the duodenum is usually stained with bile in the cadaver. Because the liver and gallbladder must be retracted superiorly to expose the gallbladder during an open anterior surgical approach (and atlases often depict it in this position), it is easy to forget that, in its natural position, the body of the gallbladder lies anterior to the superior part of the duodenum, and its neck and cystic duct are immediately superior to the duodenum.

The pear-shaped gallbladder can hold up to 50 mL of bile. Peritoneum completely surrounds the fundus of the gallbladder and binds its body and neck to the liver. The hepatic surface of the gallbladder attaches to the liver by connective tissue of the fibrous capsule of the liver.

The gallbladder has three parts, the:

• Fundus: the wide blunt end that usually projects from the inferior border of the liver at the tip of the right 9th costal cartilage in the midclavicular line (MCL).

• Body: main portion that contacts the visceral surface of the liver, transverse colon, and superior part of the duodenum.

• Neck: narrow, tapering end, opposite the fundus and directed toward the porta hepatis; it typically makes an S-shaped bend and joins the cystic duct.

The cystic duct (3-4 cm long) connects the neck of the gallbladder to the common hepatic duct. The mucosa of the neck spirals into the spiral fold (spiral valve). The spiral fold helps keep the cystic duct open; thus bile can easily be diverted into the gallbladder when the distal end of the bile duct is closed by the sphincter of the bile duct and/or hepatopancreatic sphincter, or bile can pass to the duodenum as the gallbladder contracts. The spiral fold also offers additional resistance to sudden dumping of bile when the sphincters are closed, and intra-abdominal pressure is suddenly increased, as during a sneeze or cough. The cystic duct passes between the layers of the lesser omentum, usually parallel to the common hepatic duct, which it joins to form the bile duct.

The arterial supply of the gallbladder and cystic duct is from the cystic artery. The cystic artery commonly arises from the right hepatic artery in the triangle between the common hepatic duct, cystic duct, and visceral surface of the liver, the cystohepatic triangle (of Calot). Variations occur in the origin and course of the cystic artery.

The venous drainage from the neck of the gallbladder and cystic duct flows via the cystic veins. These small and usually multiple veins enter the liver directly or drain through the hepatic portal vein to the liver, after joining the veins draining the hepatic ducts and proximal bile duct. The veins from the fundus and body of the gallbladder pass directly into the visceral surface of the liver and drain into the hepatic sinusoids. Because this is drainage from one capillary (sinusoidal) bed to another, it constitutes an additional (parallel) portal system.

The lymphatic drainage of the gallbladder is to the hepatic lymph nodes, often through cystic lymph nodes located near the neck of the gallbladder. Efferent lymphatic vessels from these nodes pass to the celiac lymph nodes.

The nerves to the gallbladder and cystic duct pass along the cystic artery from the celiac (nerve) plexus (sympathetic and visceral afferent [pain] fibers), the vagus nerve (parasympathetic), and the right phrenic nerve (actually somatic afferent fibers). Parasympathetic stimulation causes contractions of the gallbladder and relaxation of the sphincters at the hepatopancreatic ampulla. However, these responses are generally stimulated by the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK), produced by the duodenal walls (in response to the arrival of a fatty meal), and circulated through the bloodstream.