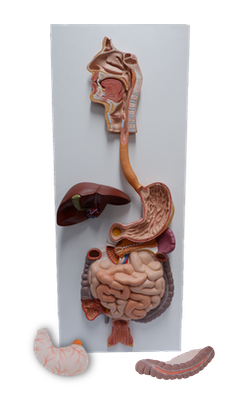

Main Model

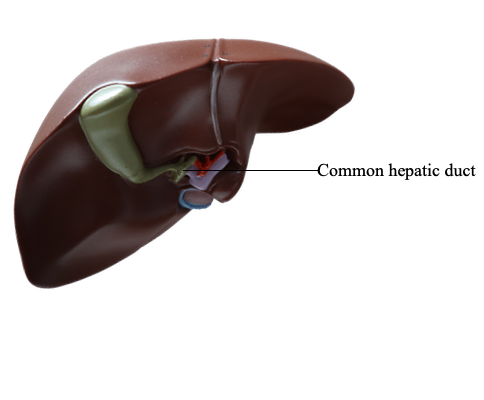

Common hepatic duct

Biliary Ducts

The biliary ducts convey bile from the liver to the duodenum. Bile is produced continuously by the liver and stored

and concentrated in the gallbladder, which releases it intermittently when fat enters the duodenum. Bile emulsifi es the

fat so that it can be absorbed in the distal intestine.

Normal hepatic tissue, when sectioned, is traditionally

described as demonstrating a pattern of hexagonal-shaped

liver lobules (Fig. 2.69A) when viewed under low magnifi -

cation. Each lobule has a central vein running through its

center from which sinusoids (large capillaries) and plates

of hepatocytes (liver cells) radiate toward an imaginary

peri meter extrapolated from surrounding interlobular

portal triads (terminal branches of the hepatic portal vein

and hepatic artery and initial branches of the biliary ducts).

Although commonly said to be the anatomical units of the

liver, hepatic “lobules” are not structural entities; instead, the

lobular pattern is a physiological consequence of pressure

gradients and is altered by disease. Because the bile duct is

not central, the hepatic lobule does not represent a functional

unit like acini of other glands. However, the hepatic lobule

is a fi rmly established concept and is useful for descriptive

purposes.

The hepatocytes secrete bile into the bile canaliculi formed

between them. The canaliculi drain into the small interlobular

biliary ducts and then into large collecting bile ducts of the intrahepatic portal triad, which merges to form the hepatic ducts

(Fig. 2.69B). The right and left hepatic ducts drain the right

and left (parts of the) liver, respectively. Shortly after leaving the

porta hepatis, these hepatic ducts unite to form the common

hepatic duct, which is joined on the right side by the cystic

duct to form the bile duct (part of the extrahepatic portal triad of

the lesser omentum), which conveys the bile to the duodenum.

BILE DUCT

The bile duct (formerly called the common bile duct) forms

in the free edge of the lesser omentum by the union of the

cystic duct and common hepatic duct (Figs. 2.65 and 2.69B).

The length of the bile duct varies from 5 to 15 cm, depending on where the cystic duct joins the common hepatic duct.

The bile duct descends posterior to the superior part of

the duodenum and lies in a groove on the posterior surface

of the head of the pancreas. On the left side of the descending part of the duodenum, the bile duct comes into contact

with the main pancreatic duct. These ducts run obliquely

through the wall of this part of the duodenum, where they

unite, forming a dilation, the hepatopancreatic ampulla (Fig.

2.69C). The distal end of the ampulla opens into the duodenum through the major duodenal papilla (see Fig. 2.45C).

The circular muscle around the distal end of the bile duct is

thickened to form the sphincter of the bile duct (L. ductus choledochus) (Fig. 2.69C). When this sphincter contracts,

bile cannot enter the ampulla and the duodenum; hence, bile

backs up and passes along the cystic duct to the gallbladder

for concentration and storage.

The arterial supply of the bile duct is from the (Fig. 2.71):

• Cystic artery: supplying the proximal part of the duct.

• Right hepatic artery: supplying the middle part of the duct.

• Posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery and gastroduodenal artery: supplying the retroduodenal part of

the duct.

The venous drainage from the proximal part of the bile

duct and the hepatic ducts usually enter the liver directly

(Fig. 2.72). The posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal vein

drains the distal part of the bile duct and empties into the

hepatic portal vein or one of its tributaries.

The lymphatic vessels from the bile duct pass to the cystic

lymph nodes near the neck of the gallbladder, the lymph

node of the omental foramen, and the hepatic lymph

nodes (Figs. 2.70 and 2.71). Efferent lymphatic vessels from

the bile duct pass to the celiac lymph nodes.