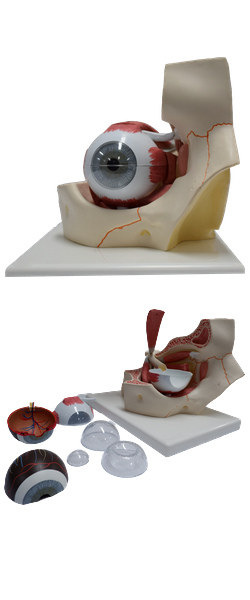

Main Model

Uvea : 6 Choroid

Vascular Layer of Eyeball

The middle vascular layer of the eyeball (also called the uvea or uveal tract) consists of the choroid, ciliary body, and iris. The choroid, a dark reddish brown layer between the sclera and retina, forms the largest part of the vascular layer of the eyeball and lines most of the sclera. Within this pigmented and dense vascular bed, larger vessels are located externally (near the sclera). The finest vessels (the capillary lamina of the choroid, or choriocapillaris, an extensive capillary bed) are innermost, adjacent to the avascular light-sensitive layer of the retina, which it supplies with oxygen and nutrients. Engorged with blood in life (it has the highest perfusion rate per gram of tissue of all vascular beds of the body), this layer is responsible for the "red eye" reflection that occurs in flash photography. The choroid attaches firmly to the pigment layer of the retina, but can easily be stripped from the sclera. The choroid is continuous anteriorly with the ciliary body.

The ciliary body, is a ring-like thickening of the layer posterior to the corneoscleral junction, which is muscular as well as vascular. It connects the choroid with the circumference of the iris. The ciliary body provides attachment for the lens. The contraction and relaxation of the circularly arranged smooth muscle of the ciliary body controls the thickness, and therefore the focus, of the lens. Folds on the internal surface of the ciliary body, the ciliary processes, secrete aqueous humor. Aqueous humor fills the anterior segment of the eyeball, the interior of the eyeball anterior to the lens, suspensory ligament, and ciliary body.

The iris, which literally lies on the anterior surface of the lens, is a thin contractile diaphragm with a central aperture, the pupil, for transmitting light. When a person is awake, the size of the pupil varies continually to regulate the amount of light entering the eye. Two involuntary muscles control the size of the pupil: the parasympathetically stimulated, circularly arranged sphincter pupillae decreases its diameter (constrict or contracts the pupil, pupillary miosis), and the sympathetically stimulated, radially arranged dilator pupillae increases its diameter (dilates the pupil). The nature of the pupillary responses is paradoxical: sympathetic responses usually occur immediately, yet it may take up to 20 minutes for the pupil to dilate in response to low lighting, as in a darkened theater. Parasympathetic responses are typically slower than sympathetic responses, yet parasympathetically stimulated papillary constriction is normally instantaneous. Abnormal sustained pupillary dilation (mydriasis) may occur in certain diseases or as a result of trauma or the use of certain drugs.