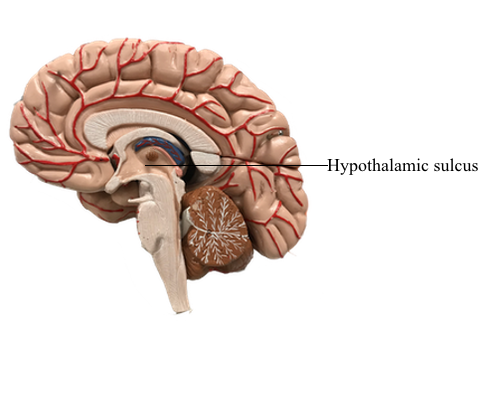

Main Model

Diencephalon : 20 Hypothalamic sulcus

The Hypothalamus

One of the most rostral cell groups to influence visceral function,

and the one that has direct input to all other visceral nuclei in the

neuraxis, is the hypothalamus. In addition to its role in regulating visceromotor functions, the hypothalamus, through a variety

of circuits, influences circadian rhythms, neurohormones, reproductive functions, general homeostasis, and behavior.

Overview

The hypothalamus is the part of the diencephalon involved in

the central control of visceral functions (through the visceromotor and endocrine systems) and affective or emotional behavior

(via the limbic system). Although its primary role is

in the maintenance of homeostasis, the hypothalamus partially

regulates numerous functions, including water and electrolyte

balance, food intake, temperature, blood pressure, possibly the

sleep-waking mechanism, circadian rhythmicity, and general body metabolism. The hypothalamus (at about 4 g) is dwarfed

in size by the rest of the brain (weighing approximately 1300 to

1400 g). However, it is perhaps the most important 4 g in the

entire body. In short, the hypothalamus influences our responses

to both the internal and external environments and is

necessary for life.

Boundaries of the Hypothalamus

The rostral boundary of the hypothalamus is the lamina terminalis, a thin membrane that extends ventrally from the anterior

commissure to the rostral edge of the optic chiasm and represents the anterior boundary of the third ventricle.

The lamina terminalis separates the hypothalamus from the more

rostrally located septal nuclei. Superiorly, the hypothalamus is bounded by the hypothalamic sulcus, a shallow groove that separates the hypothalamus from the dorsal thalamus. The lateral boundary of the hypothalamus is formed rostrally

by the substantia innominata and caudally by the medial edge of

the posterior limb of the internal capsule. Medially, the hypothalamus is bordered by the inferior portion of the third ventricle. Caudally, the hypothalamus is

not sharply demarcated, merging instead into the midbrain tegmentum and the periaqueductal gray. Externally, the boundary

between the hypothalamus and the midbrain is represented by

the caudal edge of the mammillary body. This is an especially

good landmark to use when viewing a sagittal magnetic resonance

image in the diagnosis of hypothalamic lesions.

Hypothalamus and Pituitary

Inferiorly, the hypothalamus is continuous with the pituitary

gland (located in the sella turcica and covered by the diaphragma

sellae) by way of the infundibulum and the hypophysial stalk. The infundibulum is located immediately caudal to

the optic chiasm, is somewhat funnel shaped (hence its name),

and contains a small portion of the third ventricle, the infundibular recess. The infundibulum continues into the pituitary by

a stalk of tissue that is sometimes called the hypophysial stalk.

This stalk passes through an opening in the diaphragma sellae.

The pituitary originates from two sources and directions.

The posterior lobe (pars nervosa) arises as an outpocketing

of the inferior surface of the developing diencephalon. The anterior lobe (adenohypophysis) arises as an infolding of the ectodermal lining of the roof of the developing oral

cavity (the stomodeum) and is commonly referred to as the

Rathke pouch. The smaller portions of the pituitary,

the tuberal part (pars tuberalis) and the intermediate part (pars intermedia), also originate in association with the anterior

lobe. As development progresses, these separate structures join

to form the pituitary of the adult.

Although the pituitary is well protected in the sella turcica,

it is, at the same time, subject to a variety of potential insults

(tumor, vascular, surgical) in this confined location. In addition,

the extension of the hypophysial stalk and infundibulum through

the diaphragma sellae is a vulnerable relationship. For example,

trauma to the head may result in a shearing of the stalk and the

eventual development of diabetes insipidus.