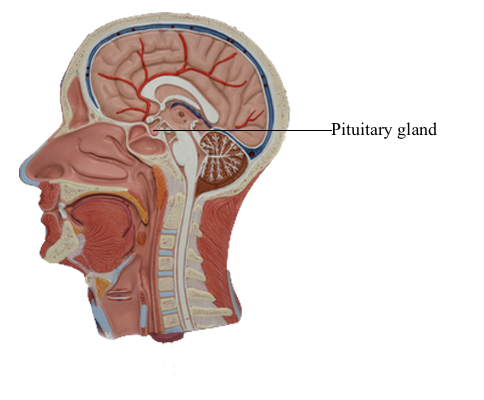

Main Model

Brain : 16 Pituitary gland

Inferiorly, the hypothalamus is continuous with the pituitary

gland (located in the sella turcica and covered by the diaphragma

sellae) by way of the infundibulum and the hypophysial stalk. The infundibulum is located immediately caudal to

the optic chiasm, is somewhat funnel shaped (hence its name),

and contains a small portion of the third ventricle, the infundibular recess. The infundibulum continues into the pituitary by

a stalk of tissue that is sometimes called the hypophysial stalk.

This stalk passes through an opening in the diaphragma sellae.

The pituitary originates from two sources and directions.

The posterior lobe (pars nervosa) arises as an outpocketing

of the inferior surface of the developing diencephalon. The anterior lobe (adenohypophysis) arises as an infolding of the ectodermal lining of the roof of the developing oral

cavity (the stomodeum) and is commonly referred to as the

Rathke pouch. The smaller portions of the pituitary,

the tuberal part (pars tuberalis) and the intermediate part (pars intermedia), also originate in association with the anterior

lobe. As development progresses, these separate structures join

to form the pituitary of the adult.

Although the pituitary is well protected in the sella turcica,

it is, at the same time, subject to a variety of potential insults

(tumor, vascular, surgical) in this confined location. In addition,

the extension of the hypophysial stalk and infundibulum through

the diaphragma sellae is a vulnerable relationship. For example,

trauma to the head may result in a shearing of the stalk and the

eventual development of diabetes insipidus.

Pituitary Tumors

The pituitary gland is anatomically and functionally linked to

the hypothalamus. Indeed, it is through the pituitary that many

hypothalamic functions are expressed. Hormones and releasing hormones manufactured in the hypothalamus are transported via

the supraopticohypophysial and tuberoinfundibular tracts and are

released into the hypophysial portal system. Small lesions within

the hypothalamus can block the manufacture and transportation

of these substances, thereby adversely affecting pituitary functions. Similarly, tumors (adenomas) occurring within the pituitary can easily encroach on the neighboring hypothalamus and

thus jeopardize its functions. It is therefore appropriate to briefly

consider pituitary tumors at this point.

Visual deficits are frequently experienced by

patients with pituitary tumors. These deficits may reflect damage to the optic nerve immediately rostral to the chiasm, to the

chiasm itself (uncrossed fibers or decussating fibers), or to the

optic tract immediately caudal to the chiasm. For example, a

pituitary tumor pressing on the optic chiasm may damage axons

originating from the nasal half of each retina. This may result in a

loss of vision in the temporal half of the visual field for each eye

(a bitemporal hemianopia), thereby reducing peripheral vision.

Tumors occurring within the pituitary gland account for 12%

of primary brain tumors. In autopsy studies, the overall occurrence of incidental (undiagnosed) pituitary adenomas has been

as high as 22.5% and as low as 3.2%, depending on the thickness of sectioned pituitary glands. In young adults, pituitary

tumors that occur most frequently are generally noncancerous.

In contrast, adenomas that occur with increasing frequency in

the fifth, sixth, and seventh decades of life are discovered as an

incidental finding.

Pituitary tumors can be classified according to their secretory

characteristics, size, or biologic invasiveness. Secreting tumors produce an excess of one or more pituitary hormones; prolactin is

the most commonly affected of these hormones. A second classification of these tumors is by size; microadenomas are tumors

less than 1 cm in greatest dimension, whereas tumors greater than 1 cm across are referred to as macroadenomas. A third classification of these tumors is according to invasiveness; invasive

tumors may erode and extend into the dura mater and even the

sphenoid bone.

Nonsecreting pituitary tumors do not secrete hormones and

as a result are often undiagnosed until they grow to a considerable size and exert pressure on nearby structures (e.g., the optic chiasm and hypothalamus). Patients with these large pituitary

tumors have symptoms that often include visual disturbances (in

60% to 70% of patients) and headaches.

Secreting Tumors

Growth Hormone-Secreting Tumors

Under normal conditions, release of growth hormone is stimulated by growth hormone-releasing hormone (GHRH) and inhibited by growth hormone release-inhibiting hormone (GHRIH),

both of which are controlled by the hypothalamus.

These factors act on the pituitary somatotrophs, one of the acidophils of the anterior pituitary, to cause the release of growth hormone, which potentially may act on all tissues of the body.

The effects of growth hormone, also called somatotropin, are

mediated by the liver through insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1, sometimes called somatomedins) with secondary effects on

peripheral tissues, especially connective tissue and bone metabolism, as well as liver metabolic activity. Whereas somatotropin

may promote growth and metabolism of fat and inhibit glucose

uptake, excessive levels may result in diabetes mellitus.

In the clinical setting, secreting pituitary tumors are also

commonly referred to as hormonally active or hypersecreting

tumors. The clinical manifestations of a secreting tumor are due

to the effects of the biologic activity of the specific pituitary hormone that is overproduced.

In cases of excessive production of growth hormone, if the

growth occurs before closure of the epiphyseal plates of the

long bones, patients experience uncontrolled growth in height

referred to as gigantism. These patients may have

large muscles, but they are actually rather weak because their

muscles contain excessive amounts of connective tissue rather

than muscle fibers.

On the other hand, the overproduction of growth hormone after the growth plates have closed results in a condition termed acromegaly, referring to the enlargement of the

digits of the patient. Patients with acromegaly

have typical facial changes, with elongation of the

face, malocclusion of the jaw, and gaps in the lower dentition.

Other changes include frontal and mastoid sinus bulges, a bulbous nose, thickened lips, and very large hands and feet. Associated with these external manifestations are

excessive cortical thickening of bone, cardiac failure secondary

to heart enlargement (cardiomegaly) as well as hypertension

and diabetes mellitus.

Thyrotropin-Secreting Tumors

A much rarer form of pituitary tumor can result from the overproduction of thyrotropin hormone. The result may be either

hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Frequently, the patients have

abnormal cardiovascular function as well as tremor. With the progression of these tumors, symptoms such as headaches, visual disturbances, and parasellar cranial nerve (i.e., cranial nerves III, IV,

and VI) dysfunction may be recognized. The cranial nerve dysfunction generally involves the abducens nerves first, then the oculomotor and trochlear nerves, as the tumor enlarges in a lateral direction.

Adrenocorticotropic Hormone-Secreting Tumors

(Cushing Disease)

During times of stress, the central nervous system acts through

a "biologic clock" to cause the hypothalamus to initiate corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) to stimulate the corticotroph cells of the anterior pituitary. In turn, these pituitary

cells release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). This hormone acts on the adrenal cortex to release cortisol, which has

a negative feedback on both the hypothalamic release of CRH

and the pituitary release of ACTH. The release of

cortisol oscillates throughout a 24-hour period, reflecting the

alternating signals from the hypothalamus. Plasma levels may be

relatively high at some times during this 24-hour cycle or relatively low. Consequently, in determination of the

level of cortisol in the blood, the time and circumstances under

which samples are taken must be considered. An overproduction of corticotropin leads to a form of hyperadrenalism known

as Cushing disease. In this instance, the excessive ACTH from the pituitary gland results in excessive adrenal cortisol secretion with the resultant classic clinical features of Cushing disease. In general, affected patients have central

truncal obesity, moon-like facies, facial hirsutism, and a dorsal

cervical hump, commonly called a buffalo hump, which results

from enlargement of the fat pad in this area. The

centropedal obesity has a hallmark finding of violaceous striae

(stretch marks). These striae are clearly different from those

seen in pregnancy or in excessive weight gain. Striae in Cushing disease are purple to violet, whereas striae in

other situations are usually pale white. These patients also have

hyperpigmentation, easy bruising, hypertension,

osteopenia, and emotional lability.

Prolactin-Secreting Tumors

An overproduction of prolactin in women results in the syndrome

of galactorrhea (milk production) and amenorrhea (absence of menstrual periods). Hyperprolactinemia is

seen physiologically as part of a normal pregnancy. However,

amenorrhea, without galactorrhea, may be seen in women who

are aggressively athletic and have little body fat; this is mediated through a different physiologic mechanism and not related to a

pathologic cause.

The hypothalamus influences the lactotroph cells of the anterior pituitary to increase prolactin production by the action of

prolactin-releasing factor (PRF) or to inhibit prolactin production through the action of prolactin-inhibiting factor (PIF). However, prolactin is the pituitary hormone that is

tonically inhibited; in this sense, the inhibitory pathway predominates. The dominance of the inhibitory pathway is interrupted during pregnancy, birth, and nursing.

After birth, the suckling reflex stimulates further PRF and promotes prolactin production, which ensures further milk production. At the cessation of breast-feeding, the PIF pathway again dominates, the suckling reflex is absent, and milk production

stops; this is usually accompanied by a decrease in breast size.

There are, however, other causes of hyperprolactinemia that

require differentiation from either tumor or pregnancy (e.g.,

hypothyroidism, drug use). In men, hyperprolactinemia may be indicated by decreased libido, impotency, or infertility. This type

of hypersecretory tumor is one of the most common pathologic

causes of infertility in men.

Gonadotropin-Secreting Tumors

The cascade of events that result in the production of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) arises from a release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) from

the hypothalamus to the anterior pituitary. Gonadotropic cells of the pituitary in turn produce LH and FSH, which

influence the ovary in the female and the testis in the male.

Gonadotropin-secreting tumors produce either excess LH

or excess FSH. Excessive secretion of FSH causes no known

symptoms in either men or postmenopausal women. However,

in menopausal women, excessive FSH release may completely

shut down the menstrual cycle. Excessive LH secretion has

been reported to cause premature pubertal changes (precocious puberty) in males and possibly disruption of the ovarian cyclicity in females. In most instances, however, gonadotroph adenomas come to clinical attention because of their mass effect, with visual impairment, headaches, and occasionally diplopia (double

vision) caused by compression of the oculomotor nerve due to

lateral extension of the tumor.

In males, the hypothalamus releases GnRH that acts on the

gonadotrophs to release both FSH and LH, which act dominantly on the testes for both gametogenic function (sperm production) and endocrine function (testosterone release). Both

of these hormonal activities can, through negative feedback,

inhibit the release of GnRH, FSH, and LH. In

females, the menstrual cycle is regulated by the hypothalamic

release of GnRH, which causes a sequential release of FSH and LH acting on the ovaries. The interaction of the cyclic release

of estrogen and progesterone with a possible role for inhibin is

intrinsically responsible for the regulated menstrual cycle.